The Cultural Holographic

Some musings on the past few decades in America and a metaphor for the next

Sometimes it feels banal or gross--given that most escaped memes come from 4chan and other far-right tunnels--to trace the lineages of the internet characters that populate the discursive universe of memes across social media today. In spite of this yuckiness, I consider it important to examine characters like Pepe, Wojak, and Milady, because who they are how and they work can help us understand the patterns of an emergent zeitgeist that is flummoxing so many.

First— how exactly should we talk about American culture today? Where are we in this mess of a thing we call society? Allow me to take stock of the recent past.

The Postmodern era reached its apotheosis with Madonna, MTV, punk, the 1990s expansion of grunge and a flourishing multiculturalism in fashion, the Talking Heads, Y2K, American Psycho (1991 book, 2000 film), the election of Bill Clinton, the possibility of a new, liberal world order with a sole superpower after the fall of the Berlin Wall, and the liberating possibilities presented by the dial-up internet (web 1.0).

Yet for all its bombast and glamour, much of this period’s most celebrated art was defined by its ever-tightening relationship with finance, costuming its neutrality in reactionary dissidence.

This was a time of great optimism — but monumental social failures are easy to find. That some of the best artists and most provocative culture-bearers of this generation died from AIDS should not be a footnote. The postmodern cosmopolitan American embraced the rhetoric of liberalization, but government at all levels stuck their heads in the sand when gay men began dying in droves, and the media buried the story until Rock Hudson got sick.

Similarly, this period saw the western world fail to adequately prevent ethnic-cleansing and genocide in less-developed parts of the globe, while tremors from global economic realignments injected turbulence into already socially and politically unstable regions. In the former Yugoslavia action came too late; in Rwanda it didn’t come at all. Towards the end of this period (2001-2008), America’s failure to act in accordance with its stated values eroded into a psychedelic stew of greed, stagnation and fantasy, as when the executive branch and military leaders invented rationales for invading Iraq while concealing its true intention to secure access to oil and in turn, make loads of money.1

Camille Paglia argues the whole cultural idea was inherently empty:

“There is no such thing as postmodernism. We remain in the era of modernism, which began in the early twentieth century with the Cubism of Picasso, the Dada of Duchamp, and German Expressionism… Young artists have been taught to be “cool” and “hip” and thus painfully self-conscious. They are not encouraged to be enthusiastic, emotional, and visionary… Postmodernism is a plague upon the mind and the heart.2

Thankfully, we are in a new era, at least ten years in by my yardstick, though many artists are only now noticing it. (That’s how cultural cycles go. Because we’re speaking in such broad and unbounded terms, one can only estimate start and end-dates. We should think of these things as peaks and valleys with significant overlaps, delays and reverberations—like seasons fading into one another.) We can now see such stark differences in today’s youth culture especially as compared with just 15 years ago that we should have little doubt we’ve entered a new period — one which lacks an agreed upon name. British theorist Alan Kirby called it Digimodernism3 but my preferred technological metaphor is not digital but holographic.

The transition into the Holographic I will argue is around the time of Obama’s election — the iPhone was introduced (2007), Kid Cudi released Day n’ Nite on his Myspace page (2008), Facebook took over from Myspace to become largest social media platform (2008), an anonymous Satoshi Nakamoto published the Bitcoin whitepaper (2008), Obama was inaugurated (2009), Lady Gaga broke to #1 with Just Dance and Poker Face (2009), and Twitter (2006) and Instagram (2010) were founded.

The seed for mainstream American thought had by 2010 shifted in the aggregate from cable TV and talk radio to internet platforms (web 2.0), from which a cascade of increasingly bizarre political and cultural events blossomed that blindsided just about everyone relying on old adages of “it is the way it is.” Within four years, the democratic party platform moved from “No” on Gay Marriage (2009) to seeing it passed popularly in the Supreme Court (2013). The Arab Spring (2010-11) took oppressive regimes by surprise as protestors organized on social media in response to an economic and authoritarian crunch. In 2016, Donald Trump tweeted dog-whistles to white-supremacy and was elected president, aided by Russian bots operating out of Glavset, its Internet Research Agency. Perhaps in response to Trump’s outmoded misogyny, corporate America found itself the target of a wave of political “wokeness” and many male public figures faced a harsh reckoning over sexual harassment and abuse during the #MeToo era (named as such because of a Twitter post and viral meme). Never the best readers of the room, big corporations made a temporary peace with the Social-Justice Warrior Left and, in contradiction to their highly conservative inner compasses, bowed to the new moral authorities by printing #StayWoke on T-shirts and turning their logos rainbow-colored during Pride month. In 2020, Covid-19 hit, and Black Lives Matter and the climate movement achieved some of the largest coordinated social actions in history, inflecting a seemingly performative sense of new passion and renewed commitment to the liberal project. And the American pro-life movement, on the back of Trump’s Supreme Court nominees, struck a major victory by overturning Roe v. Wade after laying the judicial groundwork for decades (2022).

At first quietly, but now with a cacophony that many expect to increase over the next few decades, America and Europe face frontal challenges to their western-led world-order by other superpowers. After years of pinpricks, Russian troops invaded the sovereign nation of Ukraine. In China, political leaders used Covid-19 to weaponize and expand surveillance and monitoring in a country that already squashes protests by force, criminalizes the free practice of religion, registers citizens in surveillance programs and operates concentration camps filled with Uighur people.

Stemming from over a century of rapid population growth fed by coal-fired industrialization, the world’s atmosphere is taking on CO2 and warming to new, dangerous levels.

At the fulcrum of the Postmodern and the Holographic, American cinema’s leading man transformed (one could argue regressed) from the relatively empathetic Y2K masculinity exemplified by Tom Hanks in “Sleepless in Seattle” towards the archetype of a rich, hyper-individuated and vengeful Superhero represented by Christian Bale’s Batman (2005-2012) and Robert Downey Jr.’s Iron Man (2008-2013). This uber-man hasn’t got time for love! In fact, he’s kind of a workaholic. Does this billionaire ever go on vacation? In both series, the Superhero’s romantic interest is a colleague aligned the Superhero’s mission. And they say office romance is dead!

Would anyone be surprised to learn that Christian Bale’s Batman votes Republican? That Iron Man plays golf with Trump? These guys want to go and Make America Great Again. This cinema, like large swaths of Holographic Republicanism, is nursing a nostalgic fever. Sci-fi? Star Wars. Oceans 14? Women. Sylvester Stallone still fuckin’ slaps.

But no amount of cinematic dreaming can return us to the postmodern; there will be no more ovations for lounge chairs deemed sufficiently mid-century modern. America can no longer claim it’s the only super-power, and the youth is well past admitting that those old liberal promises have—so far—failed to materialize.

On the cusp of Holographic personhood

There are many characterizations of holograms within pop-culture and many technologies that claim to be holographic. Let’s look at the etymology of the word:

holo — from holos, meaning whole.

graphic — from graphos, meaning written.

In the 1600s, holographus meant a letter written entirely by the hand of the person who signed it — a genuine text bearing unfalsifiable, physical marks of personhood.

In 1964, when the holographic method was invented, the word took on a new but related meaning. A hologram is a truly 3-dimensional photograph which encodes the light-field of a given volume over a given time frame and represents it on a glass plane. The inventor, or perhaps, discoverer of this method was Dennis Gabor:

“The basic idea was that for perfect optical imaging, the total of all the information has to be used; not only the amplitude, as in usual optical imaging, but also the phase.” (Wikipedia)

The holographic is totally representational — just as the holographos was made genuine by a lack of mediation between author and text, a holographic image is a genuine primary photograph, not a flattened 3-dimensional scene onto a 2-d picture plane, but a 3-dimensionally accurate reproduction of the physical light in a specified spatial volume from a certain perspective.

The impact of our new holographic digital sensorium, the internet as it reaches past web 2.0 and into something more advanced and spiritually and biologically active, triggers flashbacks to Walter Benjamin’s “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, as we are now entering yet another version of this liquid mirror, where previously sacred things will become as easy (and inexpensive) to reproduce as have digital images. What sacred things are next? I would argue: the way we moderate and “use” our personal identities could radically change in definition over the next generation.

Lenticular holograms, the type I used to make art — are not true 3D images but instead plastic lens arrays that afford the illusion of completeness. This is not true dimensionality but the illusion of such. And this is where we are now, in 2022, perceiving an illusion of holography. Our data bodies are enchained by web 2.0 business models because our communications are passing through tubes owned by massive, relatively simple corporations which transform our data into money by serving us ads. All our data are not belong to us… Unlike the holographus, there are rarely primary texts on the internet; our images are generally mediated, and our digital identities remain mere fragments of souls.

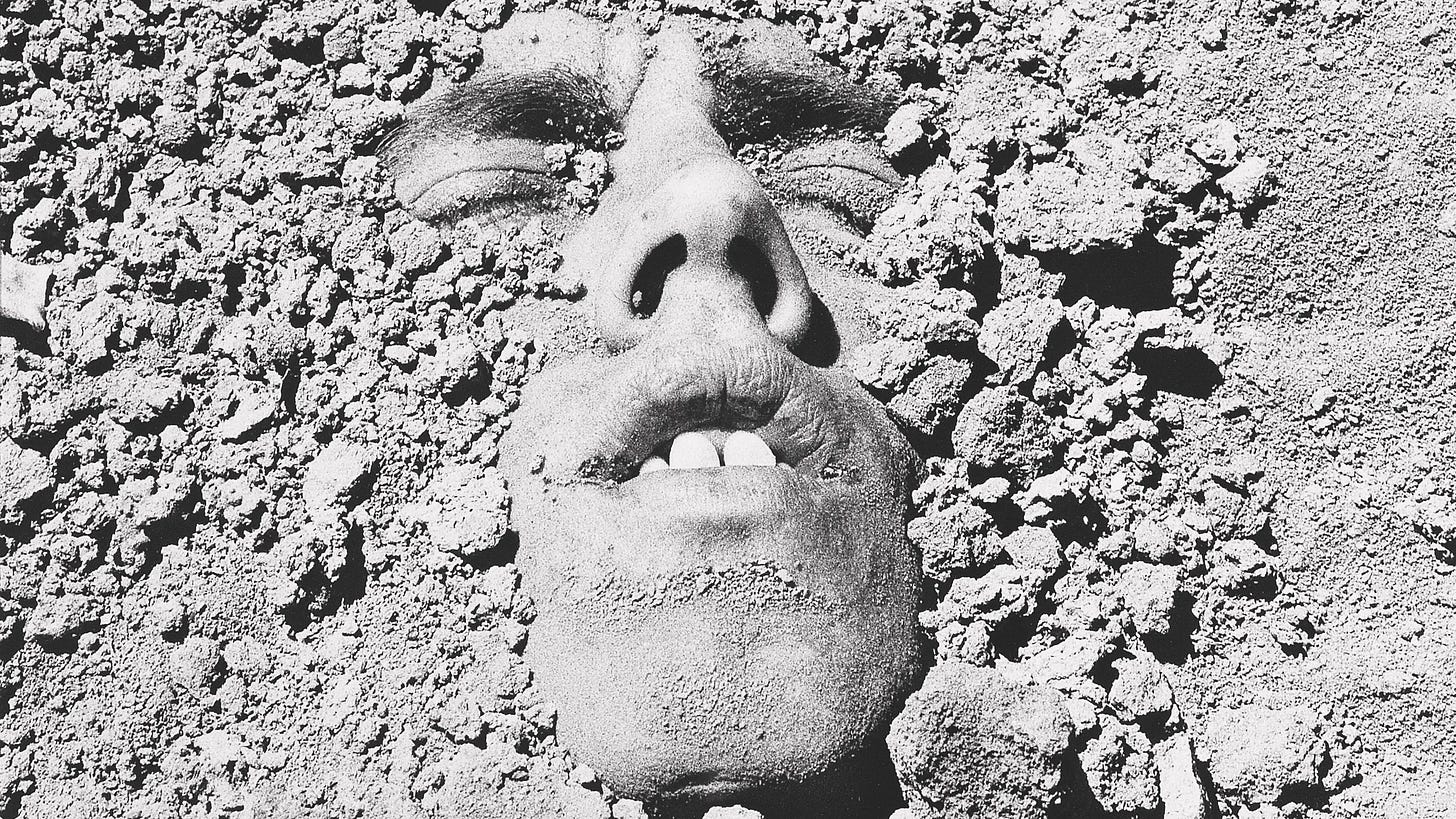

It's this discord, between the fragments we are on the internet and the whole selves we know ourselves to be as human, that leads to soul-searching in online communities like Milady and attachments to cult leaders like Charlie Fang. I suspect it’s also one reason among many that social isolation in America seems to be hitting all-time highs all the time, and why I feel the “Age of Anxiety” has still a ways to go until it turns over into something more health, regenerative, and beautiful.

https://faustomag.com/camille-paglia-postmodernism-is-a-plague-upon-the-mind-and-the-heart/

https://philosophynow.org/issues/58/The_Death_of_Postmodernism_And_Beyond